This interview with Ste Pickford was made for my swedish NES/Famicom documentary(Dokument NES). I got these answers back in january of 2014. It is published here in english so everyone around the world can enjoy it. The interview was made to get information about how games where made for the NES, so I really did not dive into Stes career as a game maker.

Ste and his brother John(the Pickford brothers) are two brittish developers. The made games for Rare on the NES as Zippo Games. These days they make games under Zee-3.

The pictures referrd to in the questions can be seen here.

/Stefan Gazimaluke Gancer

THE INTERVIEW

Q: In the early days of game development for the Family Computer Nintendo really didnt have any proper development tools. They used something called a digitalizer to input graphics, they drew the pixel art on graph paper and layed it on the digitalizer which had a grid of LED lights 8×8 and they lit a LED and then input what color the that position on the graph paper should have. Do you know anything about this digitalizer more than what I said? I know you didnt start developing NES games until later when better development tools had been created.

In the picture is Nintendos Takashi Tezuka editing graphics for Super Mario Bros 3 in 1989. What are the tools he is using?

How was graphics made for your NES games? What kind of hardware and software where used? Do you know if the methods where much different at other developers or was there som kind of universal tool set?

I don’t know anything about a digitalizer! That sounds dreadful. We never used anything like that. Although we didn’t start doing NES games until a bit later than some, we’d been making games on other platforms for several years, and never had to use anything as awful as that.

In a nutshell, what we did back then is the same as what we’d do now. We’d create graphics using a tool of some kind on a computer, we’d then use a different tool to convert the saved graphics data into a format suitable for the target platform, then import that data into the game project as it’s built or compiled for the target machine. In modern game development this process is described as a ’pipeline’. We didn’t use that term back then, but the process was essentially the same, if a bit more primitive with fewer steps.

Back in the late 1980s, for NES graphics, Rare used to use graph paper and type the data in, but they were a bit behind the times. We use DPaint 2 on the Amiga then PC to create our graphics. In DPaint I’d arrange the finished graphics on screen as a set of characters (the same way they were laid out in NES mem

ory), probably as an LBM file, and we wrote a tool in DOS to scan these screens into character set data.

For sprites I’d then also work out the ’builds’ of each frame of the sprites on paper, and manually write down the coordinates of each individual 8×8 pixel sprite that made up the ’build’ of each frame of animation.

For backgrounds I think we still mapped out levels on paper, and manually typed in the data for blocks of characters than made up each level.

Q: How was music and sound effects created? Was there some separet tools for that and what was the process of composing music? In the picture is Nintendos Koji Kondo in his office in 1989. I see a lot of hardware, but which of it did he acctually make the game music with?

Ah, I’m afraid I don’t know much about audio, as Rare provided all the finished audio for our NES games, and the programmer intergrated it into the game – a process I wasn’t involved in. I *suspect* that the audio guys actually wrote code – just like the game programmer – to directly control the audio hardware of the NES, and I think what they provided was a block of code that was included with the regular game code, so the music in the game was created by a program running, rather than merely playing data.

Q: How long did it take to make a NES game from idea to finished product? I realize it depends on the game but where there some average development time? And what was an average team size for a game?

I think we were talking about 6 months to a year back then, although it may have been a bit less than that. My memory is sometimes faulty! Typically we had just two man game development teams back then, a single programmer and a single artist who’d both create the graphics and build the levels. There was also audio, but the audio guy typically worked on several games, so wouldn’t have counted as a full time staff member for the whole of the project.

At Zippo games we probably averaged about three people per team, with myself or my brother John involved in pure game design for a certain amount of time on the project (separate from programmer and artist), and often myself or another artist joining in creating extra art or levels at a later stage.

For Wizards and Warriors 3 we actually had two programmers on there for a while, with one programmer handling all the front end in interior scenes, so team sizes were slowly creeping up from 2 to around 4 or 5 over the course of our time making NES games.

Q: How was the conversion from PAL to NTSC or vice versa done? Was it a software or hardware modification?

I can’t remember exactly, and as an artist it wasn’t something I was directly involved in, but it was a software change that we usually did at the very end, and typically took a day or so. We made the games for NTSC, and used NTSC hardware to develop on, even though we were based in the UK where our TV system was PAL. We had to get hold of NTSC TVs, which was a pain – actually Rare managed to find a source of ’multisystem’ TVs (TVs that worked with both PAL and NTSC), which were really hard to find back then, and were like gold dust in the office!

Making games for NTSC meant that we were working at a 60fps frame rate. When it came to the PAL conversion, this switched to 50fps, which meant that there were no speed problems as a 60th of a second fits easily into a 50th of a second. The overall speed of the game slowed down as a consequence though, and there were sometimes odd little timing problems that needed fixing, and I’m not sure if music needed speeding up or anything, but as I remember it was a trivial job that was done once the NTSC version was finished.

Q: What hardware and software where used to do the coding of a game? And did that differ from developer to developer? In the picture are the Nintendo EAD programming team that made SMB3 among other games. In the picture from 1989 Iv learned they use computers that are several years old, was it common to not use state of the art hardware?

Again, I don’t know much about Nintendo’s internal systems, but they were a pretty odd company, and it wouldn’t surprise me if they used odd or old hardware. Nintendo didn’t dicate how we worked, and we didn’t need to know anything about how they worked. Our job was to provide finished ROM images, that ran on the NES hardware, and our development processes were our own business.

Our development hardware was all PC based. It wasn’t necessarily ’state of the art’, but it was up to date. We juse used fairly standard modern PCs of the time – 286s and 386s (incredibly primitive now). As I said, graphics were done using DPaint 2. I think our first NES graphics were done on Amiga, but then we may have switched to PC, but I was using the same tools. For development, we used an up to date compiler / editor, and then in the case of NES stuff, Rare provided a hardware connection to a modified NES target machine, so we compiled the code on the PC, which then downloaded the code onto a fake cartridge on an NES plugged into the PC, which then ran the game. We could also burn EEPROMS with the latest version of the game onto a test cartridge, that we could take away and play on a modified NES.

Q: The NES allowed for use of different chips in the cartridge itself that could enhance what could been done with the game. How did this affect the development. Did you decide what chip should be used before development began or could it change as the development went on?

Yeah, the hardware on the cartridge was pretty cool. I know a lot of the funky animation effects in Mario 3 were done via special hardware on the cartridge that could swap out banks of memory instantly, allowing ’free’ animation of character blocks (the dancing plants and trees on the map screen for example) without taking any processor time.

Typically though this wasn’t a decision we made ourselves. Rare had their own custom cartridge design, and we made games built for the Rare cartridge.

The other big one was the amount of ROM space on the cartridge. This varied from game to game, and was usually something decided at the start of a project (as it had manufacturing cost implications), although it would often increase over the course of development. Sometimes because we really needed more space to fit the game we wanted make, and sometimes it increased because ROM costs had decreased over the course of development, so we were given extra space to fill for free.

Q: Are EPROM and EEPROM the same thing. When researching I have come across EPROMs being used but not EEPROM.

I’m not 100% certain of the difference between EEPROMs and EPROMs myself. I just remember them being referred to as EEPROMs within the studio. Probably more or less the same thing for the purposes of your research.

(I got the answer to the question after posting this text on the Famicomworld forums.

infinest: ”And isn’t the only real difference between EPROMs and EEPROMs what the name tells you? EPROM: Erasable Read Only Memory EEPROM: Electronically Erasable Read Only Memory. EEPROMs can be erased via electricity by a programmer itself and EPROMs have those windows and can only be erased by shining UV light into them.”)

Q: When you starten development of a game, how much of the story, gameplay etc. was thought of before actual coding and designing was started?

How much we planned in advance? It all depended on the game. We’d generally ’spec out’ the scope of the game at the beginning, before getting the contract, by writing a game design document which outlined the story of the game, the locations, the type of gameplay, some concept art, etc. This would form part of a pitch to get the contract. Once development begins, we’d fill in all the details, design and build the actual levels, write the script and dialogue if there was any, etc.

So at the start of, say, a big game like Wizards and Warriors 3, we knew there were going to be three disguises (thief, warrior, magician), areas of a city only accessible to each disguise, different gameplay for each disguise, etc., but only when development began did we actually implement the gameplay for each disguise, plan out the map of the city, work out the actual puzzles, write the dialogue, etc. Most of the work was done during development. It would be a waste to design too much before getting the contract, and also a mistake to get too specific (in terms of script, locations, etc.) before the game was part developed, as many aspects of script and locations naturally flow from the way the gameplay works, which you don’t know until it’s impelemted.

Q: There are some modern editors for NES graphics, that load the graphics straight from a ROM image. They all look something like this one in the image.

Q: So you had to divide larger sprites into smaller 8×8 squares and arrange them in this row by row fashion in the image editor?

Q: So for the backgrounds you made 8×8 tiles and drew up the arrangement on paper like they did in earlier days with sprites but instead of a square on the paper reprecenting a pixel it was a 8×8 tile?

As for the part about music and sound I thought you might not know much about it, Iv tried to get a email interview with David Wise but there is no answer to mails sent through his homepage.

The example you show for Kirby is the primitive method that a lot of Nintendo games used (I don’t think Nintendo were very advanced at making graphics back in the NES days). They used a grid of 8×8 sprites, with each from of the character’s animation being made up of a new grid, so frame 1 of kirby would use 4 sprites (effectively 16×16 pixels), frame 2 would use another 4 sprites (effectively another 16×16 pixels). This was straightforward and easy to understand, and easy to create the data, but didn’t really squeeze the most peformance out of the hardware. Every new frame of animation needed a new set of sprites. If you did bigger characters, say 24 x 32 pixels, you’d need 12 8×8 sprites per animation frame, and you’d run out of sprite memory, and out of sprites on the screen really quickly.

What we did was to draw the animation frames on screen (in Dpaint) then very carefully, manually, cut out the individual 8×8 sprites used in each frame, looking out for repeated sections (say, the head of a walking character might look the same in every frame of the walk animation, just be in a different position), and make up a block of sprites (like the right hand side of the kirby image), and then we’d carefully draw out the ’build’ for each frame of animation, on graph paper, noting the pixel position and sprite number of each 8×8 sprite used.

I’ve enclosed a scan of one of the many pages of sprite builds for Wizards and Warriors 3 to illustrate this.

The advantages were two-fold. Firstly we could re-use individual 8×8 sprites again in multiple frames of animation (you can see in my image that City Dweller frames 0 to 3 all use sprite 9D for the head, even though the head is in a different position each frame), and also that we never needed to draw sprites on screen for blank areas of the animation frame. If a character crouched, we drew fewer sprites on screen. The nintendo grid method meant that if a character crouched, the empty top half of the frame would still need to be drawn, even though it was empty. Also, the nintendo grid method meant the size / shape of the character was limited to the grid – so Kirby can never be bigger than 16×16 pixels. In our method, if a character reached upwards for 1 frame, we could draw extra sprites above for just that one frame.

The disadvantage was that this method was very labout intensive, and required a lot of skill and judgement to do well. It wasn’t possible to automate the process. Later, when working on the SNES, we automated the process a little, resulting in slightly less efficiency, as the SNES was a more powerful platform, and we didn’t need to work so hard to get good results out of the hardware.

There’s another example of our method on our blog:

http://www.zee-3.com/pickfordbros/archive/view.php?post=72

This shows the sprites for the flying eagle in Ironsword. You can see we only cut out 8×8 sprites on each frame for where the actual eagle’s wings are, rather than a big grid full of empty sprites that you would need using the Nintendo method.

For backgrounds, we had an intermediate step, where we’d make blocks of, say 4 x 4 characters. So a ’block’ would be made of a grid fo 4×4 characters (16 characters). and then we’d build maps out of blocks, so a map of 10 x 10 blocks, would be visually represented on screen as 40 x 40 characters, but would only be 100 bytes in memory. This is why in games like Ironsword, Wizards and Warriors 3 etc. you see repeating chunks of background, like walls and platforms and slopes, that look identical.

Hope my explanation makes sense!

Q: I wanted to ask you if you could take a look at this page and comment on some of the things mentioned.(the URL does not work any longer. The page showed of some oddities about Equinox for the SNES. A game the Pickfrods worked on. So Ste gave answers to the questions they had on the game).

I will include the parts of the Flyingomelettes article that Ste did give answers to as well.

FO: Character Changes During Game Development

FO: Character Changes During Game Development

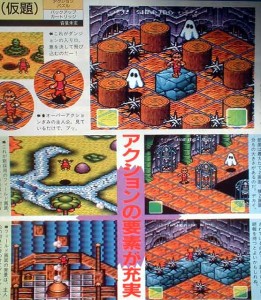

”You can clearly see that the game originally had a completely different hero. He is thinner, has different clothes, and an apple-like head with either a spike on top or a mohawk. These screenshots also depict some other changes between the early development version and the final version. The sprites for the ghost enemies are slightly different (there are no white ghosts in the first dungeon and their sheets are a little rounder and wider in the final). The floor layouts (obviously all for Galadonia) are also at least slightly different from anything in the final version. There is also something strange at the top of the screen – the name ”SHAPIRO” is written there with what appears to be Japanese lettering on both sides of it. That’s very odd considering that Equinox was made by Software Creations, a UK developer, not a Japanese company (although some of the staff do have Japanese names). I was almost tempted to think the magazine itself, which is a Japanese publication, put that text over the screenshot, but it is written in the game’s font…

It might just be coincidence, but I think the early hero looks a lot like Monster Max from the Titus game of the same name, which had a very similar gameplay style and graphics to Equinox and Solstice.”

Ste: As far as the main character goes, the original main character was drawn by me. The Japanese published didn’t like it, and offered to draw a new main character graphic for us, which they said would be better. I thought that was nonsense, and that they’d never make a better character (isometric pixel animation is hard), but the Japanese sent us their new character, and I had to admit it was miles better than the one I’d drawn. So, we put their graphic in to replace ours, quite late in development, There was no connection to Monster Max. I’ve never heard of it, never played it, and had no connection with Titus.

FO: The Case of the Missing Director?

FO: The Case of the Missing Director?

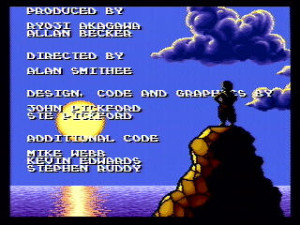

Equinox is a fantastic SNES adventure game, and one of my top favorites. But maybe not everyone else thinks the same way. Take a look at the name of Equinox’s director in the end credits:

Ste: The Alan Smithee thing is something else. We originally designed the game to be a proper JRPG style game, and each ’pot’ on the rotating landscape was actually a village. Entering the village would lead to an area with several huts with rooms inside, several NPCs, and a hidden dungeon entrance. We had a whole serious of puzzles based around the NPCs, who’d talk to you, and there’d be this whole ’overworld’ adventure and story to play through, and each puzzle you solved would unlock access to one extra dungeon entrance. We had it all specced out, designed, puzzles constructed, dialogue written, and translated into japanese. We had some really funny puzzles planned. Then, as the schedule panned out, it looked like we were going to be two or three months late. The publisher panicked and insisted we pull features from the game to get it released on the original date. The only possible way to do it was to remove the overworld adventure layer entirely (as although some graphics had been drawn, that was the only area that hadn’t been coded yet), and instead of each ’pot’ leading to a village, just make them dungeon entrances. So basically, half of the game was removed – all the adventure and story and puzzles and NPCs, leaving only the 8 dungoens. John and I were absolutely gutted, and felt like our potentially great game had been butchered. So that’s why we put the Alan Smithee name in the credits.

There’s nothing especially interesting about the other things on the page. There might be a few bugs and graphics glitches, although I can’t remember. John and I designed the game, but we had no involvement at all in the original Solstice, and the designer of that game had left the studio before we arrived. I don’t think I even played Solstice for more than about 5 minutes. I only learned enough of the story of that game to try and make this game a sensible follow up, but I wasn’t really interested in the Solstice story, or particularly trying to continue it, I was trying to design my own game. Any inconsistencies in plot / story between the two games are just my incompetence.

Hope that helps explain some things!

Other interviews with Ste Pickfrod:

http://playingwithsuperpower.com/ste-pickford-interview/